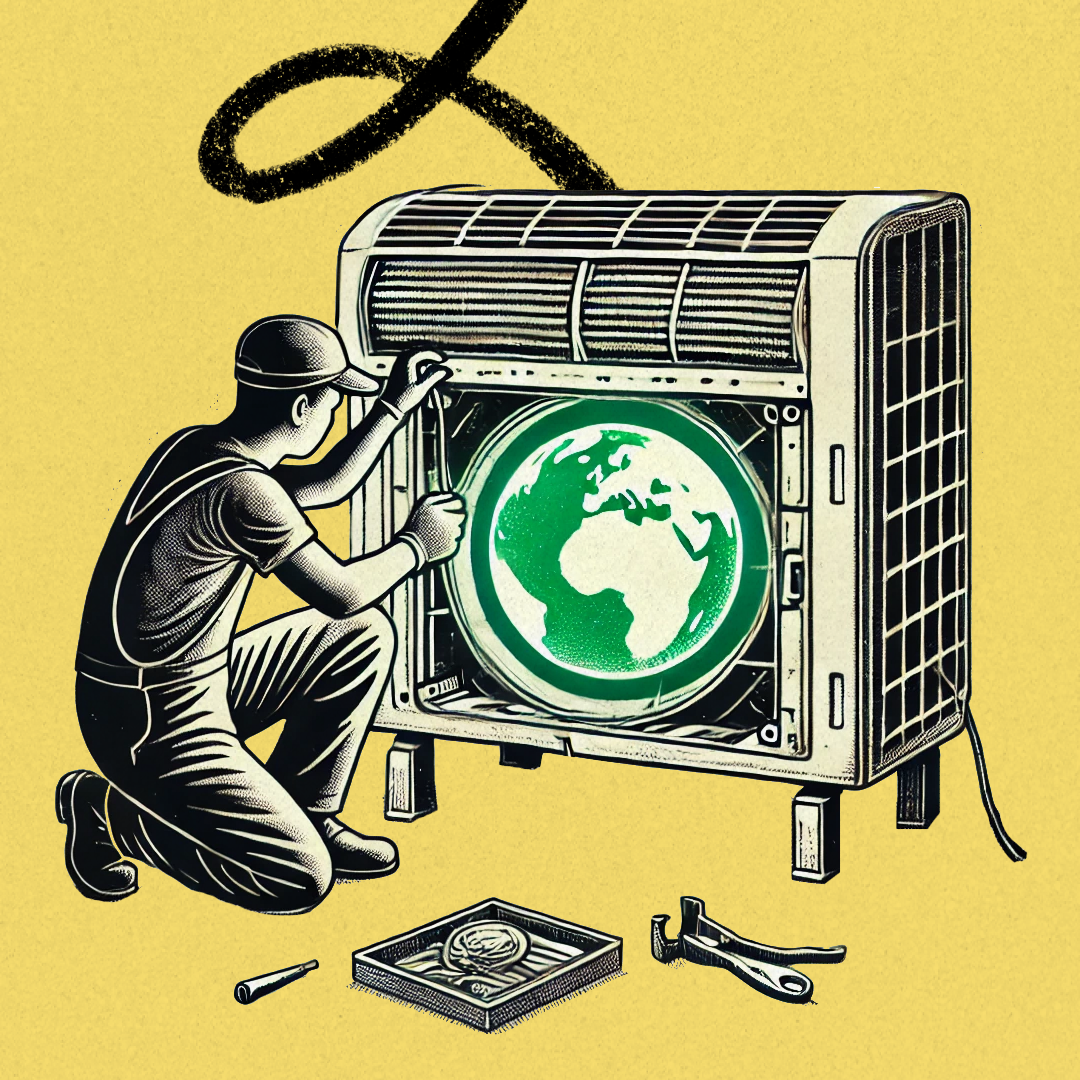

Sometimes life takes you to unexpected places, and you don’t know that next job, that next trip, that next move until it stares you in the face. That’s the story of Louis Potok, a data scientist who built a company that aims to prevent more emissions than Russia produces annually, simply by properly disposing of air conditioner fluid. It’s also the story of Jamie Wong, an early Figma engineer who was Potok’s angel investor, and the author of this piece, the second and final part in a series. (Read part one.) Potok followed a how-to book’s first suggestion of addressing the global refrigerant crisis fully down the rabbit hole, which took him around the world to Southeast Asia. This piece is a refreshing look at two people who followed an “unsexy problem” no matter where it led them.—Kate Lee

Louis Potok is, as he puts it, “attracted to unsexy problems.” Flipping through the opening pages of the book in front of him, he found one. It wasn’t flashy, but it was “so doable.”The book, Drawdown, was a guide to the 100 most pressing climate solutions of our time. Potok stopped on the first entry and knew he had found what he was going to do next.

Potok was never a prime candidate to devote his life to repairing the environment. He was born in Manhattan, and as a child, spent far more time with books and computers than communing with nature. After finishing an economics degree at the University of Chicago, he joined a nonprofit Harvard University spinout called ideas42, where he was tasked with applying behavioral economics to problems in international development. The job took him to Ghana and Malaysia and the Philippines, chatting with locals to try and ferret out problems with microfinance interventions, like small loans to market vendors.

In the course of this work, he began to peruse the literature on its efficacy. He discovered the charity evaluator GiveWell, which became his gateway into the world of effective altruism, a kind of philosophical commitment to ameliorating the world’s problems in ways that will help the greatest number of people in the greatest possible way. Soon he was browsing through online rationalist forums such as LessWrong and looking for career advice on the website 80,000 Hours. His dominant reaction: “I like these people.”

He loved his on-the-ground international development experience at ideas42, but chafed at spending half his time writing grants that would be read once by a grant program officer and then never again. Drawn by the promise of faster-paced work environments and rationalist ideologies, he departed Manhattan for San Francisco.

In the Bay Area, he joined a fintech startup with a mission to “disrupt the broken debt collection industry.” Later he led data science at a healthcare startup called Agathos to improve the consistency of care that patients receive between different medical providers. These were all unsexy problems.

In 2019, in the office of a nonprofit data science organization where Potok volunteered in his spare time, he pulled a book from the shelf. Drawdown is a compilation of 100 climate solutions ranging from the obvious (solar and wind power) to the surprising (family planning and improved cattle feed). Each solution comes annotated with the magnitude of greenhouse gas emissions it could prevent and the economic cost of implementing it. The quantified approach to addressing climate change appealed to both Potok’s inner data scientist and his inner economist. After flipping through the pages, he bought himself a copy.

Potok’s idea was to work through Drawdown, item by item, reading up on the proposed solutions before searching to make sure companies were working to address them. He planned to move from number 1 to 2 to 3, and so on, until he found a climate problem that was woefully unaddressed.

He never made it past the first item—a problem much more severe than commercial aviation and far less discussed. It was so doable.

The book that sparked a climate change mission

Potok’s San Francisco bedroom was one Scarface poster short of being a typical 29-year-old guy’s quarters. Tidy but minimally adorned, a place to sleep rather than a place to relax. It was here, in 2019, that he began his investigation in earnest, with a fresh copy of Drawdown on his desk.

The book was opened to a two-page glossy spread titled “Materials: Refrigeration.” The right-hand summary statistics informed him that the opportunity ranked number 1 of all the solutions cataloged in the book. Refrigerants—the substances pumped around inside air conditioners and refrigerators to transfer heat from one place to another—are potent greenhouse gasses. If they reach the atmosphere, they warm our planet just as carbon dioxide does, but more intensely. Refrigerants constitute nearly 6 percent of all emissions. That’s three times more than all emissions from aviation.

Drawdown isn’t just a catalog of problems, it’s a catalog of solutions. In the case of the refrigeration section, it highlighted disposal via thermal destruction. At extremely high temperatures, refrigerants decompose into much less environmentally harmful compounds. Here was the crux of the game: If we throw the refrigerant into a fire before it floats into the sky, we win. If it ends up in the sky in its normal state, we all lose.

As Potok worked through the history of refrigerants and collected his notes, he realized that the problem of refrigerant disposal had a few appealing properties, and one extraordinarily inconvenient one.

First under the pros column: Disposal doesn’t require any groundbreaking technology. In 1987, international scientists and policymakers devised a protocol for destroying refrigerants—most of which involve integration into existing chemical processes. Cement kilns can be modified in a straightforward manner, and they’re both plentiful and geographically distributed. Responsible disposal is already part of standard practice in the United States as part of EPA regulations. Equivalent regulation just doesn’t exist yet in much of the world.

The second boon is that solving this problem doesn’t require changing buyers’ behavior. It doesn’t require convincing billions of people to go vegetarian, or to take a staycation instead of an exotic beach getaway. Nor does it require millions of small business owners to make bets on novel building materials or new agricultural practices. People simply don’t know and don’t care what happens to their refrigerant once it leaves their air conditioners.

The incredibly inconvenient property is that the only benefit of refrigerant disposal is preventing global warming. You can’t sell a Tesla of refrigerant disposal. Responsibly disposing of refrigerant simply cannot be cheaper or easier than the alternative of letting it leak into the atmosphere. So how do you get anyone to pay for this?

In his ongoing research, Potok discovered that a company called EOS Climate had been paid to dispose of refrigerant in the past. EOS Climate hunted for old tanks of now-banned refrigerants and destroyed them. They were responding to a bounty established by the California government to destroy refrigerants as part of the state’s climate commitments.

Potok found a second-degree connection in his network who had previously worked at EOS Climate. When he asked for the mutual contact for an introduction, the mutual relayed the response: “Tell Louis this is a solved problem.”

Potok was skeptical. While he found a few companies hunting for and destroying refrigerants, there was a glaring lack of companies operating in Asia—a region that is rapidly getting hotter and richer, building toward a massive deployment of air conditioners. And nobody was positioned to prevent the enormous emission of greenhouse gasses that will result.

The problem was important—absent intervention, refrigerants would continue to contribute more to global warming than aviation does. The problem was neglected—despite the importance, a paltry few companies were working on the problem, and none in Asia. And lastly, the problem was tractable—no groundbreaking technology was needed, and there was precedent for companies being paid for this work. It was doable. All Potok needed was a little push for him to actually do it.

The first nudge came from attending Effective Altruism Global, a conference for adherents to the ideologies that created organizations like 80,000 Hours and GiveWell. Years later, Potok still remembers a fellow attendee telling him about his plans to bioengineer shrimp to feel less pain. If that guy could alter a genome for animal welfare, Potok thought, surely he could throw some chemicals in a fire—even if it required him to move to Asia and start a company first.

The second nudge came from meeting with a personal mentor from the data science nonprofit that Potok had been using as a sounding board throughout his refrigerant explorations. While Potok was verbally unloading his latest batch of insights, his mentor stopped him and asked, “How old are you? Thirty?”

Potok replied, “Twenty-nine.”

“You’re young. Go do it,” his mentor advised.

In the fall of 2019, Potok gave his two-week notice at Agathos and booked a flight to Cambodia.

Become a paid subscriber to Every to learn about:

- Why refrigerants pose a greater threat to our climate than aviation

- The winding path from San Francisco to Jakarta to build a refrigerant disposal startup

- The challenges of raising money for an unconventional climate venture

- The power of persistence in addressing unsexy but critical problems