Hello, and happy Sunday! It’s high summer in the United States, and much of the country (not to mention the rest of the world) is or will be under a heat dome. Evan and I have been sweating it out on the east coast, hoping our air conditioners hold up, while Dan has been in Rome (where ACs are comparatively less prevalent) for an Aspen Institute conference. If you want to feel a sense of hope while you pray for the humidity to drop, scroll down for a heartwarming story about refrigerant emissions (really!).

On to everything (else) we published this week, along with our take on the latest tech and business news.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Knowledge base

🔏 "Why Talk to Customers When You Can Simulate Them?" by Chris Silvestri: Ever wish you could read your customers' minds? AI might be the next best thing. Chris shows how to use large language models to create detailed customer personas, test marketing copy, and uncover hidden insights—all in hours instead of weeks. Read this if you want to turbocharge your market research and create messaging that truly resonates with your audience.

"Paramount's Dilemma: Content Isn't King—Distribution Is" by Evan Armstrong/Napkin Math: The former Hollywood giant is getting an $8 billion lifeline, but it might not be enough. Paramount's new owners may think content is king, but history shows that distribution is the real crown jewel. Between block booking and launching TV networks, Paramount's past success came from controlling how—not just what—people watched. Read this for a fascinating look at how the internet broke a century-old business model and why even Top Gun: Maverick can't save Paramount from the attention economy.

🎧 "The AI-powered Era of Scientific Discovery Is Here" by Dan Shipper/Chain of Thought: In this episode of AI & I, Dan dives deep into how large language models like BrainGPT are transforming neuroscience with professor Bradley Love. Dr. Love argues that AI could revolutionize how we approach scientific discovery, such as in predicting experimental outcomes or challenging our need for simple explanations. Listen to this if you want to understand how AI might reshape the future of science—and why that future might be less about elegant theories and more about powerful predictions. 🔏 The transcript of this episode is for paying subscribers.

"Searching for Signal" by Evan Armstrong/Napkin Math: Have you ever had that gut feeling about a startup, even when the odds were stacked against it? It turns out that that irrational instinct might be your best compass. Evan tells the story of Clay, a $500 million company that succeeded because its founders trusted their intuition over cold, hard data. Read this if you want to learn why emotion, not just strategy, is crucial for startup success—and how to tap into that "divine belief" in your own work.

"The Business (and Social Good) of Destroying Old Air Conditioners" by Jamie Wong: Jamie—an early Figma engineer-turned-investor—chronicles Louis Potok’s journey from data scientist to climate entrepreneur, tackling the unsexy problem of refrigerant disposal in Southeast Asia. Read this for a refreshing look at how following an idea down a rabbit hole can lead to meaningful climate action—and maybe make millions.

Fine tuning

An AI startup—with actual revenue! One common complaint on the tech corners of X is that AI startups are all funding and fluff, with no actual customers. Hebbia, which enables you to attach LLMs to data rooms where investment info is stored and pull out facts from due diligence documents, is the violation of that asinine assumption. The technology makes it so private equity funds or private credit investors can decide whether they want to invest much more quickly. I’ve heard from multiple investors that it transformed their diligence process. The company just raised $130 million from Andreessen Horowitz at a $700 million valuation.

Wait, what the hell even is an AI startup? In 2002, every new software company was a “cloud company.” In 2024, every startup claims to be an “AI company.” But what does that mean? I’m increasingly convinced that unless you are explicitly in the business of training and selling LLMs, you are not an AI company. Take, for example, Captions, a video-editing application that automates parts of the editing workflow and can translate the accompanying audio into other languages. It just raised $60 million valuing it at $500 million. While it calls itself an AI company, I would argue that that is just the sizzle of the product—what it really does is make video editing easier.

It’s robot time. We’ve been chatting for a while about how VCs are deploying capital with the idea that robotics are about to dramatically improve using similar techniques as LLMs. (Do you believe this? If so, reach out to me at evan@every.to—I’m working on an article analyzing the technology.) Skild AI is the latest example of a startup going after the AI-and-robots opportunity, raising $300 million from the most prominent firms of Sand Hill Road including Sequoia, Lightspeed, Coatue, and Jeff Bezos’s family office. Frankly, I love seeing this sort of thing get funded. Watching investors get more comfortable underwriting science risk is a welcome change from the 2010s.

Farewell, OpenAI board, we hardly knew ye. Both Microsoft and Apple were on the OpenAI board for the length of time I could keep a woman interested in high school (roughly one month). They both left their seats recently over concerns over antitrust laws. I also have to believe that there is a growing recognition by Altman that these companies are frenemies, with emphasis on the latter part of the word. Both companies are training foundation models, too.

Video game stocks ripping. While most of the gaming industry has been gripped by layoffs, the Korean developer behind 2024’s Stellar Blade went public this week, with its stock up almost 50 percent. I’ve argued for a while that distribution, not content, is king. Here is a counterpoint. The company has no real distribution advantages, and its job is to just make great games, which it has done so far. My theory does allow for this kind of success, but you can make becoming 10 times bigger 10 times easier by owning distribution platforms versus making the stuff that resides on them.—Evan Armstrong

Data mining

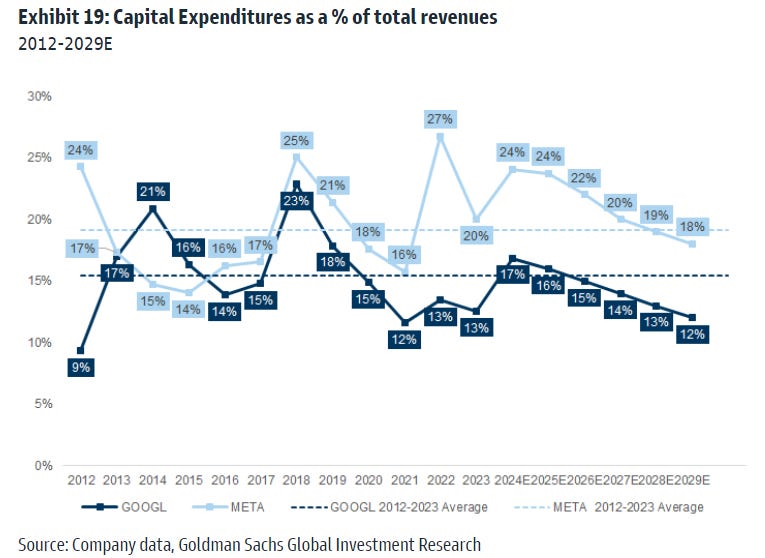

On the bubble. While it’s true that big tech is investing lots of money in AI without much to show for it (yet), they’ve done it before. As a share of revenue, current AI investments aren’t that crazy:

Source: Goldman Sachs.For both Google and Meta, current spending as a percentage of revenue is high, but it’s within the normal range of the past 10-15 years. Google (and Amazon and Microsoft) invested a lot in the cloud before they started selling it in meaningful amounts—Microsoft’s Azure took seven years to generate ChatGPT-levels of revenue. Ask people at Meta about the company’s big investments in the metaverse or stablecoins, and see how those worked out (spoiler: Meta is doing fine). So big money is being spent on AI, but these are big companies with a lot of money to spend. Will they have some egg on their face? They might, but they’ve been down this path before.—Moses Sternstein

Keyword extraction

Nat Eliason, author of the new memoir Crypto Confidential: Winning and Losing Millions in the New Frontier of Finance (which he initially chronicled on Every), shared his top three tips for internet writers who want to write a book:

Practice fiction writing. It’s much harder to take a reader through a 300-page book than a 2,000-word article. You have to study storytelling, and the best way to learn how to write better stories is to write more of them. Studying and practicing fiction writing was by far the most helpful thing I did for making the book an exciting read.

Get off the internet writing-dopamine hamster wheel. When you write for the internet, you rarely have to wait more than a few days, or even hours, to start getting feedback. Likes, shares, comments, emails—you might not realize how deeply your sense of accomplishment hinges on these signals. But writing a book is a long, slow, lonely process. Practice working on longer-term work now so the shock isn’t as severe.

Do it before you’re ready. Writing a book feels like something you have to “be ready” for, but—like having kids or starting a business—there’s never a right time. You can only become ready by doing it. The two, three, four years it might take are going to pass anyway. It’s better to start sooner than keep putting it off.

Alignment

Story mining. The most common type of feedback I receive about my writing is, “A personal story would be really good here,” or its evil twin, “This piece is crying out for an anecdote.” Yes, a personal story would be good here. And so would stabbing me repeatedly with a rusty spoon dipped in lemon juice. Writing anecdotes is hard because I have to trawl my memory to find something relevant, and then I agonize over whether the story is good enough or if I've just wasted an hour of my life on a dead end. But the power of a good story in your writing is undeniable. It's the difference between dry facts floating in the void and information that sticks. To crowbar out my personal gems, I've stolen a technique from Mike Taylor, a prompt engineer and writer at Every. He uses ChatGPT to interview himself to find personal anecdotes that give his essays a punch. Not only does this make the writing process smoother, AI points you directly to the good stories in half the time—like having a GPS for your memories.—Ashwin Sharma

Sentiment analysis

Evan’s piece about Clay garnered a lot of feedback from entrepreneurs:

“Just had something like this click for me in the last few days—getting into building React apps with Claude. The most important realization: This is so much fun, I can literally do this all day and not get tired of it.”—An AI founder

Want to chat? DM Dan or Evan on X.

Collaborative filtering

Work with us at Every. We’re hiring a full-stack designer who can work across different products, projects, and initiatives. You should move fast, be scrappy, know AI, and most of all, love Every. The ideal candidate has 1-5 years of experience, and is excited to grow with us and turn ideas into reality. Since we're bootstrapped, compensation will scale as the business scales. If you’re interested, email Lucas Crespo at lucas@every.to with your portfolio, salary expectations, and why you’d like to join us.

Hallucination

Weather Windows, a weather app UI that can be minimally displayed over glass.

Source: X/Lucas Crespo.That’s all for this week! Be sure to follow Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.