Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

It has been 161 days since I confidently declared that Apple’s Vision Pro was the future of consumer electronics. It has been 148 days since I boldly argued that the Vision Pro did not need a killer app to succeed. It has been 89 days since I loudly proclaimed that Apple had the making of a hit on its hands.

Now, it is time for me to eat crow. I was wrong—on the timing, at least.

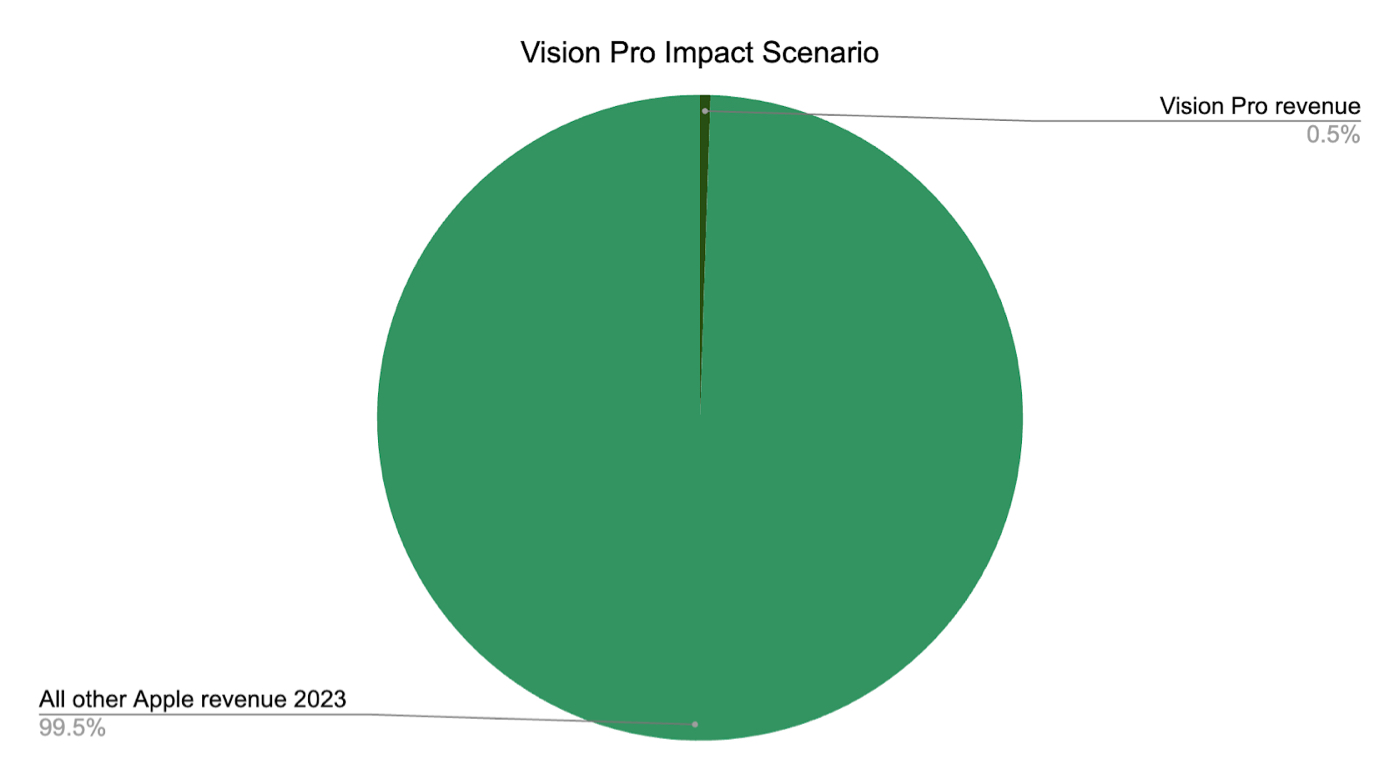

Last week, Bloomberg reported that the Vision Pro would sell fewer than 500,000 units in its first year of release. Assuming an average revenue per device of $4,000—$500 above the base model’s U.S. price, to account for currency fluctuations and device upgrades—and that Apple optimistically manages to move 500,000 units, its impact looks something like this if added to Apple’s 2023 revenue:

Source: Apple’s SEC filings and author’s napkin math.Relative to the $383 billion that Apple earned in the last fiscal year, a best-case scenario for the Vision Pro is like a Republican trying to vote in San Francisco—which is to say, inconsequential. And lest you think I’m casting stones on newly invented technology, when Apple released the iPhone, the company sold over 1 million iPhones within 74 days of its release.

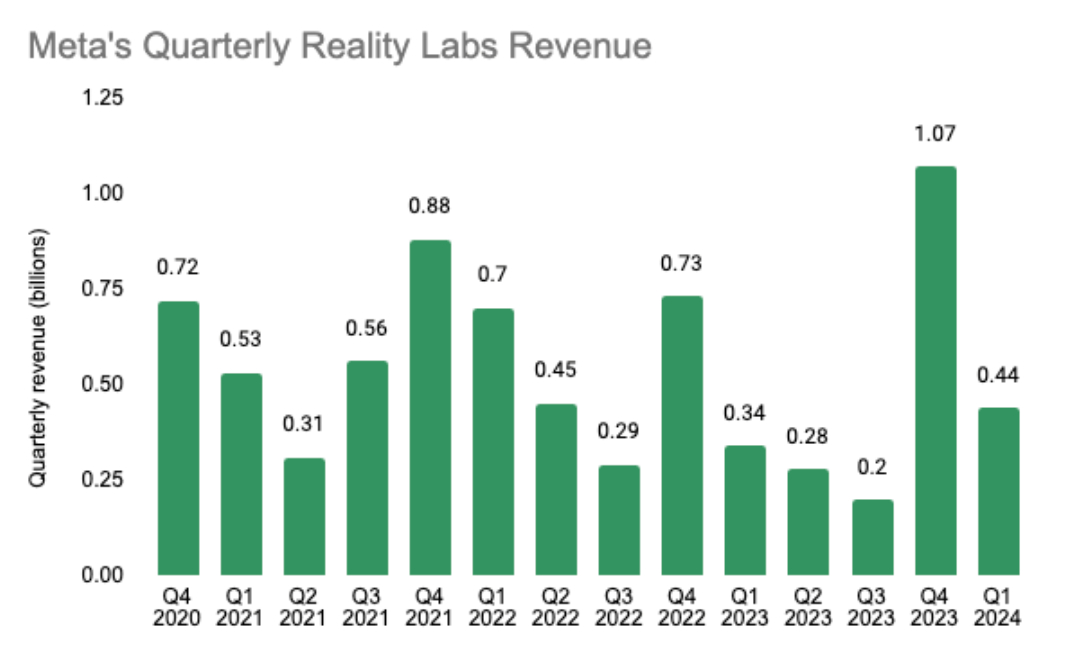

The other reason for which I’m eating my words is that I overestimated how close we were on the science. In a recent interview with analyst Matthew Ball, Meta CTO Andrew “Boz” Bosworth said that inventing the new technology required to sell hundreds of millions of units of VR “is probably the greatest challenge that our industry has approached in certainly my lifetime and my generation.” It hasn’t exactly been a consumer hit, as the data reveals: Meta’s Reality Labs’s paltry sales total $7.5 billion since the fourth quarter of 2020, in comparison with the $134.9 billion in revenue it did in the last year alone. This includes the well-reviewed Meta Ray-Bans and VR headset Quest 3. Between this and Apple, you are looking at a virtual reality market for hobbyists—the tech simply isn’t there yet.

Source: Meta SEC filings (no napkin math required).

There are three reasons for which virtual reality devices have not managed to hit expectations—each of which indicates something not just about VR, but the future of technology.

The three factors holding back VR

What can be is pretty burdened by what has been. Virtual reality, unlike personal computing innovations like the iPhone and the Macintosh, is not a clean break from what already exists. It is a technology that is only possible within the context of the internet. Network effects from previous technology paradigms translate fairly neatly into VR because the devices are reliant on the data and user profiles linked to the internet. Certain consumer internet companies like Netflix will continue to be popular, regardless of the state of VR technology. I’ve previously called this effect “big screen everywhere,” where VR will grant you the ability to interact with your preferred service or content on the best screen you’ve ever had, anywhere you want.

However, this context also makes it harder for new applications to break through. Developers are competing not only with any new applications that the hardware enables, but also with the other participants in the attention economy that are porting over their network effects. As a hardware maker, you are forced to compete on how much more useful and better your “big screen everywhere” is compared to existing options, like smartphones or laptops. Your VR headset won’t have many unique and cutting-edge applications because developers have only minor incentives to make custom things for your device. This is bad for VR because…

The science isn’t advanced enough (or why my “no killer app” idea was wrong). I have yet to try a VR device that doesn’t make me physically uncomf. The tech isn’t advanced enough, forcing device makers to make serious tradeoffs—whether the compute happens on your head, how long the battery lasts, or how clear the screen is. As a result, devices are often too heavy (like Apple’s) or tethered to computers (like the Bigscreen Beyond headset).

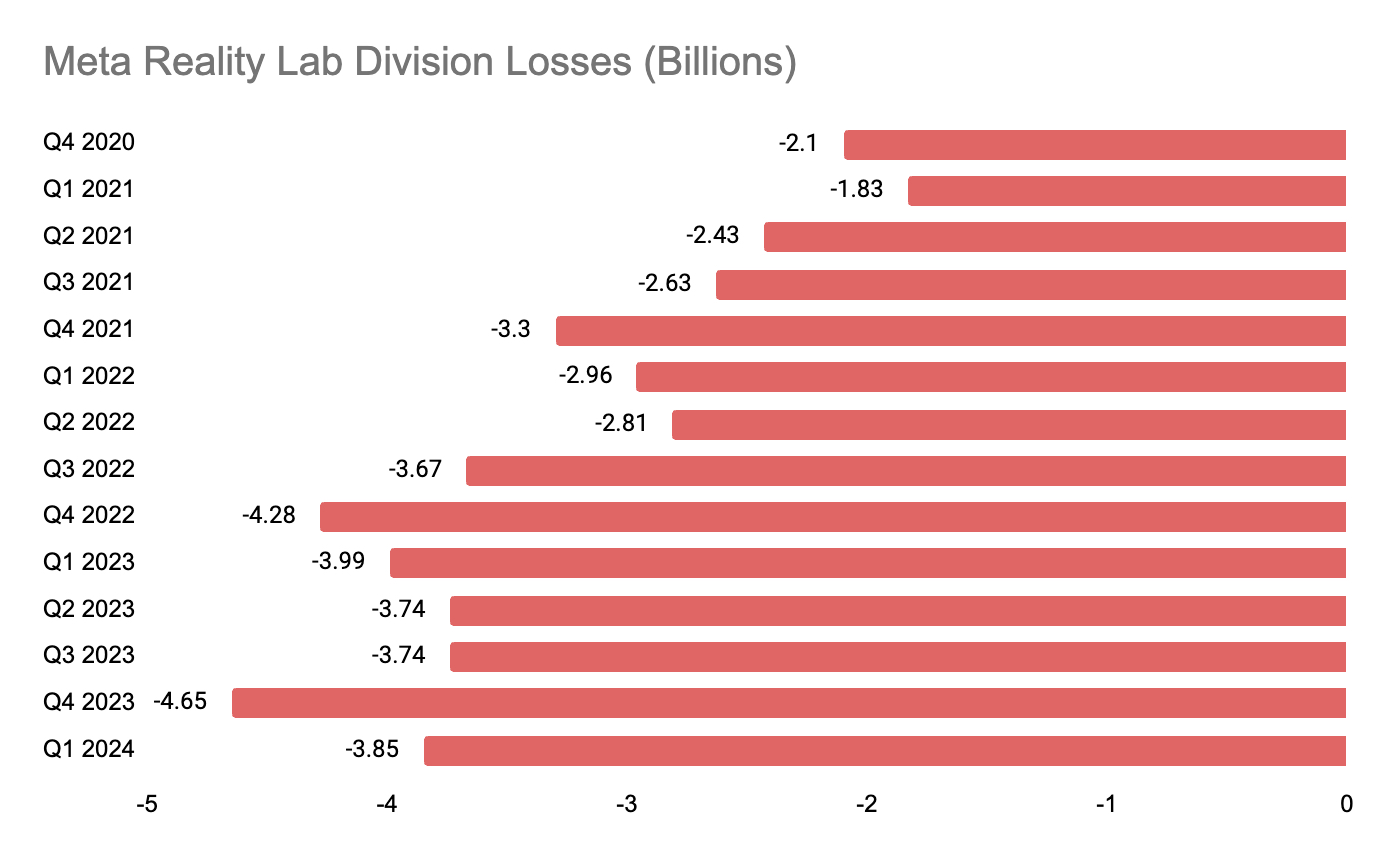

When internet network effects diminish the incentives to develop a killer app for VR headsets , the axis of competition isn’t purely VR—it is all of personal computing. For the headset to be truly competitive with an iPhone, there must be scientific advancements in multiple tech trees, like battery life. But this kind of investment is wildly expensive and uncertain, which is why Meta has lost $46 billion in its Reality Labs division since the fourth quarter of 2020.

Source: Meta SEC filings and Every illustration.Science is just plain hard. While some VR hardware startups compete by producing radically different combinations of components than the tech giant—such as focusing on making the headset as light as possible to the exclusion of everything else—these moves are not long-term defensible. If a startup breaks out with a form factor that the tech giants don’t have, it will do so on the back of the supply chains the tech giants helped develop—so the big companies will have no problem copying the startup’s success. The challenger companies have to hope that their device is able to attract a developer ecosystem exclusive to them to compete.

I prefer the tradeoffs the Vision Pro made of being untethered to a computer and heavier to maximize the size of the screen, but it also costs $3,500—a price totally inaccessible to the average American.

These two dynamics together constitute the classic strategy case of the cold start problem: Supply-side developers won’t create custom apps until demand-side consumers start buying in droves. Consumers aren’t willing to buy in droves because the price-to-utility ratio isn’t justifiable.

When I wrote my initial analysis, I overestimated the utility that regular consumers would derive from the device. I am an admitted film addict. Movies are one of my biggest passions, and because the Vision Pro is so incredible in the format, I got a little bit over my skis in my thinking. While the device is useful for productivity and focus, it isn’t good enough to justify the price point. Recent reports claim that Apple is planning to release a device at half the price next year. If it can keep the pixel quality at the $1,250 range, the Vision Pro 2 could be the device that finally gets mass adoption. (I doubt it, but theoretically, it’s possible.)

Still, I have one final, very fuzzy, very non-Napkin Math concern with the category.

These devices might be spiritual death

As I’ve written previously, my wife and I are becoming parents this fall. This is happening so quickly that over the past few months I’ve been rapid-fire examining and pruning the weeds in my life’s garden. I sold my PS5 (and pulled a gift of the magi by giving the cash to my wife so she could buy maternity clothes), lost weight, and quit watching junk TV. When my daughter comes, I want her to have a dad that fills her with wonder and pride, not one who is unable to pay attention to her.

For my entire life, computers have not been a portal to another world. They have just been the world. They were my life. I relied on them for everything outside of my hiking habit—they were work, play, friends, and study all in one magical 25-inch monitor. Now, my relationship with electronics is changing. More and more, they feel like a necessary utility that enables me to accomplish my tasks. Each time I sit down in my office to do electronic labor, I think about how it takes me away from being present with my wife and future child.

And that is the fundamental issue with any virtual reality headset or mixed reality device. It is ultimately a machine designed for selfish consumption, a visual separation from reality. Every moment I spend enjoying the latest Mad Max movie on my Vision Pro is a moment of lost connection with my wife when we could be watching it on television together instead. Said simply: This shit is creepy to look at!

Source: YouTube/Apple.It may be just me, but I can feel a shift in the technological psychosphere. People are starting to feel differently about their devices. There is a recognition that AI-generated content—aka "slop"—is melting our neurons. Devices that facilitate our dopamine addictions are going to be cast aside. Devices like “light” phones, “dumb” tablets, and bricks that block access to apps on your device are the capitalist formation of these energies, but more than that, the combination of LLMs and social media is causing us to seriously re-examine our relationship with screens.

I no longer feel that the ideal vision of VR is one in which we see our whole lives through the device—where we socialize, get the news, and spend our days. The positive vision of VR is that it becomes a purely utility device: We use it for work, we watch a movie with it, and we put it away when we’re done. But without the scientific breakthroughs I discussed earlier, it might just become a very expensive and isolating way to watch Netflix.

Frankly, my position may evolve. It could be that when my daughter is old enough, I’ll find myself too busy to parent all the time. Maybe I’ll introduce her to Fortnite. However, it’s telling in its own right that my first instinct as a soon-to-be father is that I don’t want her anywhere near this stuff.

Evan Armstrong is the lead writer for Every, where he writes the Napkin Math column. You can follow him on X at @itsurboyevan and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.