|

Hey Travis,

As I get further along in my career, I have become better able to notice how decisions from long ago can have big implications many years later. Here, I connect the dots between early U.S. drone regulations and a possible ban on the most popular drone company in the world.

-Jason

Last week, the U.S. House of Representatives jammed a functional ban on DJI drones, called the “Countering CCP Drones Act” into a military funding bill that it then passed. The bill would put DJI drones, which are made in China, onto a Federal Communications Commission “covered list” alongside other banned Chinese tech companies, meaning that new drones would not be approved to use the communications infrastructure they need in order to operate. The ban could possibly ground existing drones, as well.

This potential ban is a uniquely American clusterfuck that is arguably even worse than the TikTok ban in its absurdity because of the specifics of how we got here: There is no evidence that China is spying on DJI drones, the drone features that make lawmakers worried about “spying” were originally introduced because of U.S. regulations and government pressure, and, for drone hobbyists, there are not really any American-made drone alternatives that can step in to replace DJI’s spot in the market.

Elise Stefanik, one of the members of Congress sponsoring this legislation, has said “DJI poses the national security threat of TikTok, but with wings.” The Department of Justice and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s warnings on DJI does not provide any actual evidence of DJI spying or insecurities. Their warning largely boils down to the fact that the drones are “controlled by smartphones and other internet-connected devices, [which] provide a path for [drone] data egress and storage,” that people sometimes fly these drones over sensitive areas, and that China has a law that allows the government to demand data from Chinese companies.

We can only do these sorts of investigations with the direct support of our paying subscribers. If you found this article interesting or helpful, and you want us to keep producing journalism like it, please consider subscribing below. You’ll get unlimited access to our articles ad-free and bonus content.

Essentially, the US government pressured drone manufacturers to implement privacy and safety features that required internet infrastructure to operate, DJI built those features, and now lawmakers say those same features could be used by China to spy on Americans and are the reason for the ban. Meanwhile, the only existing American drone manufacturers create far more invasive products that are sold exclusively to law enforcement and government entities, which are increasingly using them to conduct surveillance on American citizens and communities. This means that we may face a situation where hobbyists, small businesses, and aerial photographers who make a living with drones can suddenly no longer fly them, but cops will.

I have covered government regulation of drones off-and-on since 2013. As DJI’s Phantom drone began to be integrated into American skies, the FAA and various state and local governments started to make regulations about who could fly a drone, where they could fly them, and for what purposes. I wrote many articles about early lines in the sand that the FAA drew.

At first, there were simply “guidelines” for drone operators which did not actually have the force of law behind them. The FAA then began to say that drone hobbyists could fly more or less anywhere, but “commercial” drone operators could not. But the FAA also did not have any process by which a commercial drone pilot could get authorization to fly legally. This created a bizarre situation where you could fly a drone legally, but if you sold the images or videos you took, you could be fined or otherwise punished by the FAA. The FAA had very uneven and bizarre enforcement of these rules, and some people who were essentially YouTubers posting cool drone videos or real estate agents taking photos of their listings ended up getting cited. There was quite a bit of chaos and confusion in the industry, because the FAA would say that it saw the commercial appeal of drones but, for years, did not allow people to legally fly them for commercial purposes.

At the same time, a small subset of hobby pilots started flying their drones like idiots. People flew their drones over baseball stadiums, near airports, above wildfires, and active crime scenes. There were many news stories—some of which I wrote—about people flying their drones in dangerous ways. The pilots of these drones were almost invariably flying DJI Phantoms and DJI Phantom 2 drones, which happened in part because they were the most popular drones at the time and in part because DJI drones were very easy to fly. DJI would regularly implore their customers to fly responsibly, lest the entire hobby/profession be banned before it could really take off.

Drone manufacturers, including but not limited to DJI, asked the FAA to make its rules clearer, or to make rules at all. With a string of high-profile cases where its drones nearly caused plane crashes or crashed into crowds of people and facing possible additional government restrictions, DJI introduced a “No Fly Zone” feature and, later, additional geofencing restrictions to comply with FAA regulations. To do this, DJI had to turn its dumb, non-internet-connected drones into gadgets with GPS and internet connections. Experts who have studied DJI’s geofencing and tracking systems see them as a direct response to U.S. government regulation.

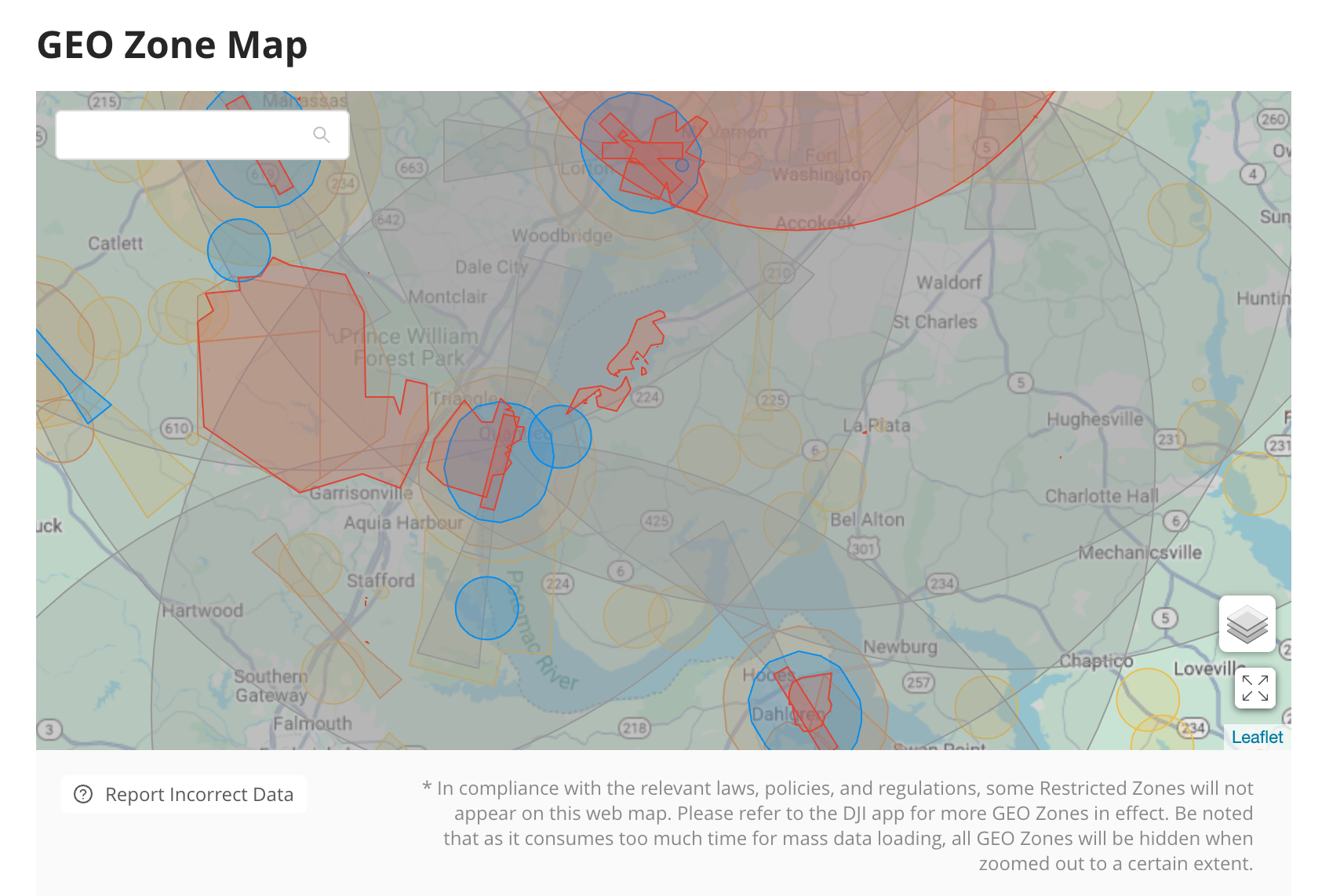

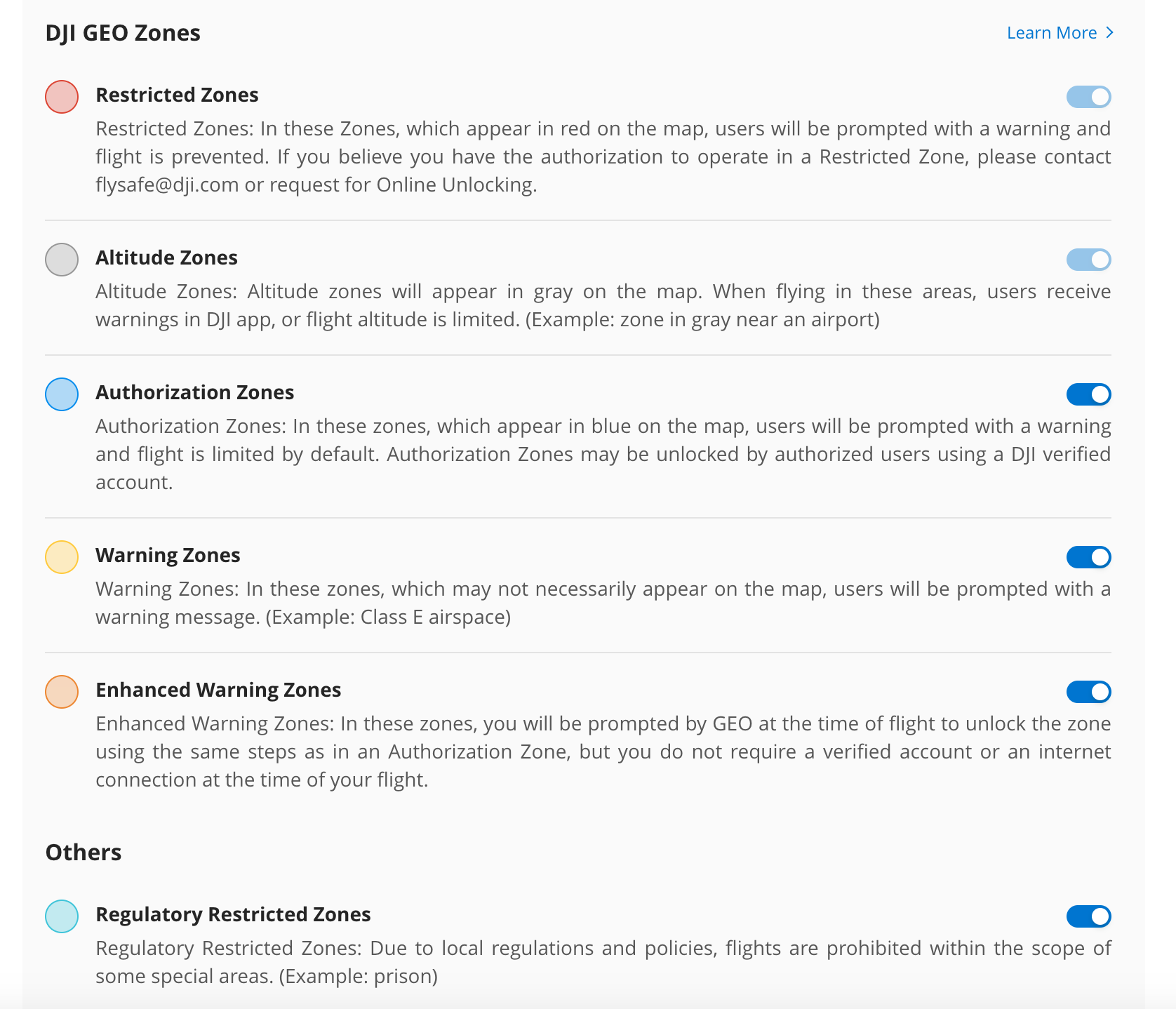

These features are connected with third-party temporary flight restriction maps which receive information directly from the U.S. government about where aircraft can and cannot fly. DJI essentially gave the U.S. government the ability to determine where its customers could fly their drones, and, if you look at DJI’s “GEO Zone Map” now, you will huge swaths of the United States have been demarcated as “Restricted Zones” where the drone simply will not fly, “Altitude Zones” where their altitude is limited, “Authorization Zones,” Warning Zones,” “Enhanced Warning Zones,” “Regulatory Restricted Zones” (over prisons, for example), and “Recommended Zones,” where flying is less restricted.

DJI has continued to add more restrictions and features to comply with U.S. government restrictions and regulations over the years. DJI drones (and most every drone) now needs to be registered with the FAA. DJI has, over the years, lobbied against many of these restrictions, but it has also proactively introduced features to prevent further regulation from the U.S. government. When rolling out some of these features, DJI has told customers that it does not give data to law enforcement or the U.S. government “unless there is a specific reason to. In the event of an aviation safety or law enforcement investigation that compels us to disclose information, our verification partner may provide information about the credit card or mobile phone number used to verify the DJI account that unlocked an Authorization zone at the location, date, and time in question. This creates a path to accountability in the event of an incident without requiring burdensome up-front collection of personal information.”

DJI has in recent weeks rolled back some of these features, presumably to make the argument that it no longer collects information that the U.S. government could consider to be sensitive. DJI did not respond to a request for comment for this article.

The fact that this technology exists had already made things much more complicated for DJI. By restricting where its users can fly drones in some areas, DJI has necessarily introduced a technology that allows it to track its customers' drones and to restrict where they can be flown. This may initially seem like an obviously good thing to do, but it also means that DJI needs to make decisions about what entities it will take no fly zone recommendations from and which it will not. It has had to decide, for example, whether Ukrainians can use DJI drones in the war with Russia, or whether it will restrict operations in parts of Iraq and Syria where ISIS has strapped bombs to DJI drones. (There is also a thriving market and underground for jailbreaking DJI drones to not have these restrictions.)

Drones have been used to automatically surveil homeless encampments, teens being loud, and house parties. Drones have been automatically and accidentally deployed to investigate a “water leak” and a person “bouncing a ball against a garage.” The drones powering this persistent surveillance are not DJI’s. They are increasingly Skydio’s.

The infrastructure and connectivity required to create geofencing, GPS features, and flight tracking technologies, which were largely introduced under intense public relations pressure, U.S. government pressure, and to comply with U.S. regulations, are now being held up as the main threat vector through which China could theoretically “spy” on DJI users, though there is no evidence that this has ever happened. Again, U.S. intelligence’s warnings about these drones focus on the fact that they connect to the internet.

The other early impact of these safety and geofencing features, though, is that DJI has become the only viable mass market drone manufacturer in the United States. There are DIY drones and racing drones, but the overwhelming majority of hobby drones on the market are made by DJI. Most of DJI’s main competitors are also Chinese. This is in part because geofencing and altitude restrictions made DJI drones more foolproof, easier to fly, and safer to use. Essentially, DJI made a better product than its competitors and now dominates the market. (There is one new hobby drone made by an American company, called the Blackhawk 3, but it has not yet found much of a market and most reviews say that comparable DJI drones are cheaper and better).

More powerful but more complicated drones like those made by onetime competitor 3D Robotics failed to find a user base, and that company no longer exists. Skydio, an American company that sells drones exclusively to cops and first responders, has fully shelved its hobby products. Consumer products from other drone manufacturers have similarly failed. This means that we are now in a situation where, if DJI is banned, there are few options ready to step in and replace it, because all of the companies that would have replaced it have utterly failed to provide the type of experience that the U.S. government demanded and is now upset about. A recent post on the Drone Girl blog, which has been covering the industry for many years, points out “There are no consumer drone companies in the U.S. worth talking about right now.”

As with TikTok, this deep fear of China comes alongside the total abdication of privacy invasions that are being enabled by American companies. While Skydio has shelved its hobby drone, it has ramped up its work on drones for cops, and has used the fact that it is not Chinese as a selling point. Last year, Skydio spent $560,000 lobbying Congress and has spent $170,000 so far this year.

In 2022, I did an investigative report into Skydio about how it uses cops to promote its drones to other cops, and how it has been developing increasingly automated drones for “Drones as First Responder” programs in which drones will automatically fly to the scene of a suspected crime.

Skydio has positioned itself as an American-made alternative to DJI for cops, and emails I obtained for that story noted that Skydio’s vice president of regulatory and policy affairs joined the company from the U.S. Department of Justice and immediately began pitching the Pentagon about the fact that Skydio drones are not Chinese: “We’re still far more secure than Apple iPhones, which are designed here but made in China, as you know,” the Skydio official wrote in an email I got using a public records request. Purchasing memos from police, meanwhile, noted that "Chinese-based drone platforms offered for sale and in use in the US have the potential to pose a significant data security risk to the user,” and that Skydio was a better alternative.

Skydio’s drones are also more autonomous than DJI’s drones, and make up the backbone of many cities’ “Drones as First Responders” programs. These programs are designed to automatically deploy drones when there is a 911 call or another police surveillance system suspects a crime. WIRED reported earlier this month that in Chula Vista, which has championed drones as first responders, drones have flown over every block of the entire city, often hundreds of times. Drones have been used there to automatically surveil homeless encampments, teens being loud, and house parties. Drones have been automatically and accidentally deployed to investigate a “water leak” and a person “bouncing a ball against a garage.” The drones powering this persistent surveillance are not DJI’s.

The drones powering this persistent surveillance are not DJI’s. They are increasingly Skydio’s. And this technology and these programs are being increasingly proliferated by police officers who act as quasi-salespeople for an American company that stands to benefit greatly from the perception that DJI’s drones are spying on ordinary Americans on behalf of the terrifying Chinese Communist Party using features that the U.S. government pressured the industry to make for its own purposes. Skydio now says its drones are used by 320 public agencies in all 50 states. And, Wednesday, Skydio announced a “National Security Board” to help it work more closely with the U.S. military.

In a video posted last week, Skydio’s CEO Adam Bry posted a video in which he said “the scale and scope of deployment is hitting another level” and that “we’re seeing NYPD do full drone as first responder with Skydio drones flying out of docks autonomously in response to 911 calls.” In that video, he adds that these drones can now “see at night in zero light,” that they will be equipped with red-and-blue police lights, and that “we’re going to ship our speaker and microphone accessory which gives you bidirectional communication,” meaning the drones will record not just video, but sound also.

He adds “DJI drones at their core are designed to be manually flown. One of the things that we think is really important for a successful DFR program to reach scale is autonomy, which is of course something we bet really big on at Skydio.”

And so, like America does best, we are ignoring the real threat at home to freak out about an imagined one from abroad.

|