Artist focus: Duccio di Buoninsegna master of the Italian Gothic

06-26-2024

Artist focus: Duccio di Buoninsegna master of the Italian GothicPart 1 of Siena in the 1300s; a new beginning

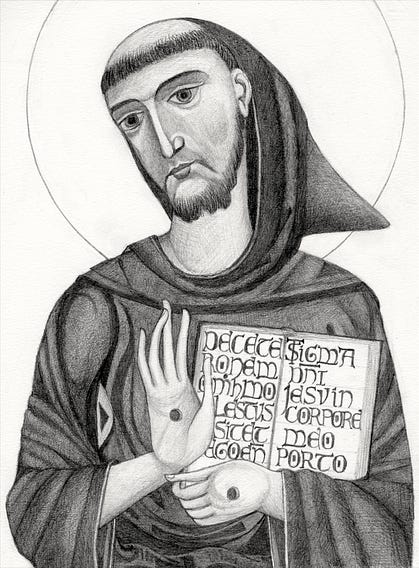

Duccio di Buoninsegna (c. 1255–1319), a Sienese painter of the late 13th and early 14th centuries, is considered one of the greatest artists of the Italian Trecento¹ and a pivotal figure in the development of Italian sacred art. In today’s post for free subscribers we’re going to have a deep dive into this pivotal and definitive painter of the Trecento, what was going on in the Christian world at the time that influenced his work, and how we can see it today as a kind of western ideal for sacred art suitable to the Latin Church and liturgy. Duccio is often credited with founding the Sienese school of painting, which was known for its detailed and decorative style and rejection of the intellectual trends that led to Florentine Humanism, sticking with the ancient principles of Christian sacred art. His work influenced many later artists, including Simone Martini, Lippo Memmi, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, who carried forward his stylistic innovations. Duccio's works represent a cornerstone of Italian medieval art. The Sacred Images Project looks at art history and Christian culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art.A big thank you to all who have signed up as free subscribers, and hello to our new paid members. Your contributions not only make it financially possible for me to continue this work, but are a tremendous encouragement to me that other people out there take these subjects as seriously as I do. This is my full time work, and I rely upon subscriptions and patronages from readers like yourself to pay bills and keep body and soul together. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable ebooks, high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.Right now only about 4.8% of all our nearly 3000 subscribers are paid members. This is well below the sustainable 5-7% for Substack.I hope you will consider taking out a paid subscription to help me continue and develop this work.(For those in straightened financial situations, fixed incomes and vowed religious etc., I’m happy to help. Drop me an email explaining and I can add you to the complimentary subscribers’ list.)The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio site, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.Like, my drawing in the Duecento style St. Francis of Asissi…Master of the blending of Byzantine and GothicDuccio di Buoninsegna emerged during a time when Italian art was heavily influenced by Byzantine traditions. His work must be understood within the context of the late 13th and early 14th centuries, a period characterized by both adherence to and gradual departure from these Byzantine styles. Duccio is celebrated for his vibrant use of colour and the emotional depth of his figures. His paintings often depict tender interactions between the Virgin Mary and Christ Child, using Byzantine iconographic prototypes in more expressive, ways with softly rounded, individualized faces and gentle, lifelike expressions. Duccio is also known for his ability to tell complex religious stories through clear and detailed compositions. He used multiple panels to create visual narratives that were accessible to a wide audience. While rooted in Byzantine traditions, Duccio’s work showed an increasing interest in natural three-dimensionality and linear perspective. However, his style retained a distinct decorative quality that set it apart from later naturalistic approaches. His work is characterized by the use of rich, highly saturated colours², detailed and expressive faces, and a combination of Byzantine and Gothic elements with typically Italian swirling, flowing lines in drapery. His works feature a balance of a strong use of line and a careful attention to the details of clothing and architecture and softer more three dimensional modelling of faces and figures.

He played a significant role in moving away from the more abstract and formal Byzantine style towards a more expressive mode. His work laid the groundwork for future Sienese painters like Simone Martini and had a lasting impact on the course of Italian art. Influences: Italo-Byzantine, or Duecento, the painting of the 13th century embraces Franciscan naturalness…

Italian sacred art of the mid-thirteenth century was still strongly influenced by the art of the Byzantine empire, under which the Italian peninsula was nominally governed until the 8th century. Italian Gothic art was, effectively, Italo-Byzantine, with gold backgrounds, hierarchical compositions, flattened or “reverse” perspective and stylized figures. The Byzantine tradition imbued Italian sacred art with a sense of solemnity and spiritual otherworldliness, emphasising the transcendent nature of religious subjects through formal, canonical poses and an ethereal atmosphere. However, by the mid-thirteenth century, the start of Duccio’s working life, Italian artists began to infuse their work with subtle shifts towards greater naturalism and emotional expressiveness, with softer, more rounded and modelled figures and faces. This was a period of artistic transition, as seen in the works of artists like Berlinghiero of Lucca, and the Master of St. Francis, who started to blend the Byzantine aesthetic with emerging Gothic influences north of the Alps, paving the way for a distinctly Italian Gothic style that would flourish in the Trecento.  Depictions of St. Francis of Assisi from the Duecento. Franciscan spirituality combined with Italo-Byzantine formalism created a kind of iconographic prototype depicting the saint that was popular at the height of Franciscanism's influence in central Italy.

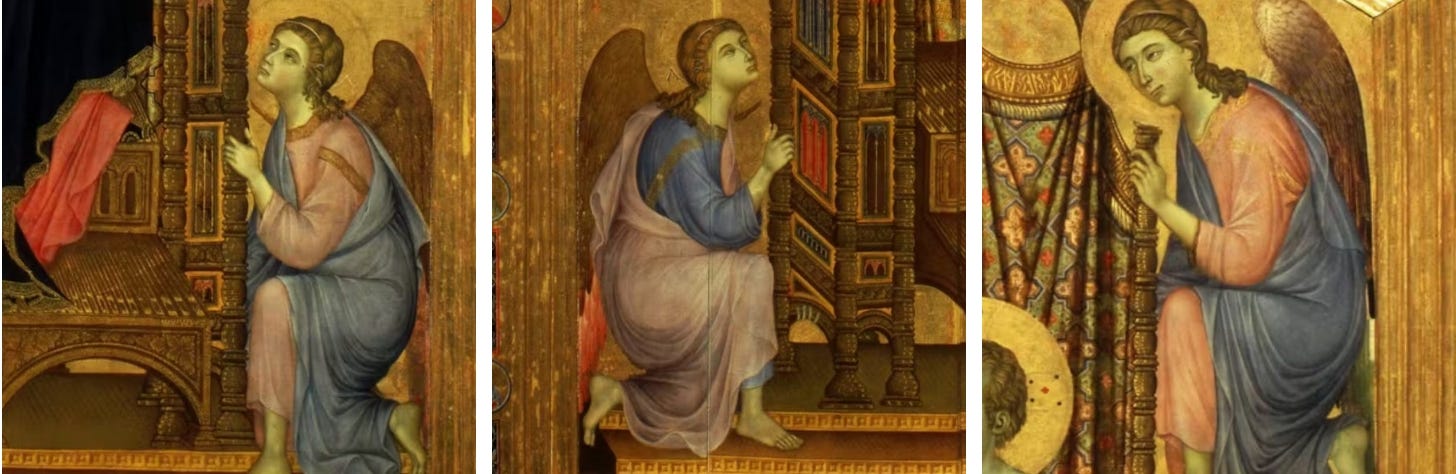

St. Francis and 13th century artThe shifts in painting style towards greater naturalness³ and emotive content during the mid-13th century in Italy, especially in the central regions of Tuscany and Umbria, were strongly influenced by the explosive growth of Franciscan theology and spirituality. This growing acknowledgement of the role of natural affections in Christian spirituality strongly influenced the development of medieval Italian painting. Franciscan theology emphasized the humanity of Christ and the humility of the Virgin Mary and the saints. Especially influential was the Franciscan devotion to Christ's passion, suffering, and the humanity of His sacrifice, which inspired artists to portray these themes with vividness and emotional intensity. Major Works The Maestà (Majesty) is Duccio's most famous work, commissioned for the high altar of Siena Cathedral. It is currently housed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, the cathedral’s museum. It is a large, double-sided altarpiece featuring scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary and Christ.  The front features the Virgin enthroned with Child and surrounded by saints and angels. The back contains scenes from the Passion of Christ.  The Rucellai Madonna (1285) (now held by the Uffizi) was commissioned for the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence by the Compagnia dei Laudesi, one of the many confraternities of laymen whose public good work included the singing of daily songs of praise to the Virgin Mary in the church.   Also called the Madonna of Santa Maria Novella, it is a large panel painting showing the Virgin and Child enthroned with angels. It exemplifies Duccio's early style, with a blend of Byzantine and Gothic influences. The Crevole Madonna (c. 1280–1285): an example of the Hodegetria iconographic prototype. The Hodegetria (from Greek, meaning "She who shows the way") is a type of icon in Byzantine art where the Virgin Mary holds the Child Jesus on her left arm and gestures towards Him with her right hand, indicating Christ as the way to salvation. Jesus is seated on Mary's left arm and reaches up to gently touch His mother’s face symbolizing the divine between mother and son, indicating Mary’s status as the Theotokos, the Mother of God. Here’s a little post from a few years ago on my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art, showing my own first attempt to do a version of this painting on paper in egg tempera with gold leaf. Thanks for reading. This is the first of a series of posts for free subscribers looking more deeply at the Italian, and specifically Sienese Trecento, or 14th century, a school of art that is often referred to only as a precursor to the Florentine Renaissance. But at this site we do not adhere to the “Whig” theory of art history in which all roads lead to, and from, the Italian Renaissance. So we will be looking at these works and artists in the context of their contribution to the western tradition of Christian sacred art itself. Next week we will look more closely at three painters who followed Duccio, Pietro Lorenzetti, Guariento di Arpo and Lippo Memmi.

1

Trecento (“tray-chent-oh”) is an Italian abbreviation for “milletrecento” - one thousand three hundred, or as we would say the thirteen-hundreds, the 14th century.

2

Colour saturation refers to the intensity or purity of a colour. A highly saturated colour is vibrant and strong, while a colour with low saturation appears dull or muted. Colours can be pictured as existing on a spectrum from pure pigment (fully saturated) to grey (no saturation). So a bright red, unmixed with blue or green from the opposite side of the colour wheel that dulls the saturation, would be high saturation, while a pale pink (a lot of white mixed in) would be low saturation.

3

I’m carefully using “naturalness” rather than “naturalism” to help distinguish between the artistic development and the later infiltration of philosophical Naturalism, antithetical to Christian sacred art. You’re currently a free subscriber to The Sacred Images Project: Early Christian Art and Culture. To see all the posts, deep dives, videos, chats and receive access to special downloads, upgrade your subscription. It’s just $9/month. |