Artist Focus: Simone Martini

07-03-2024

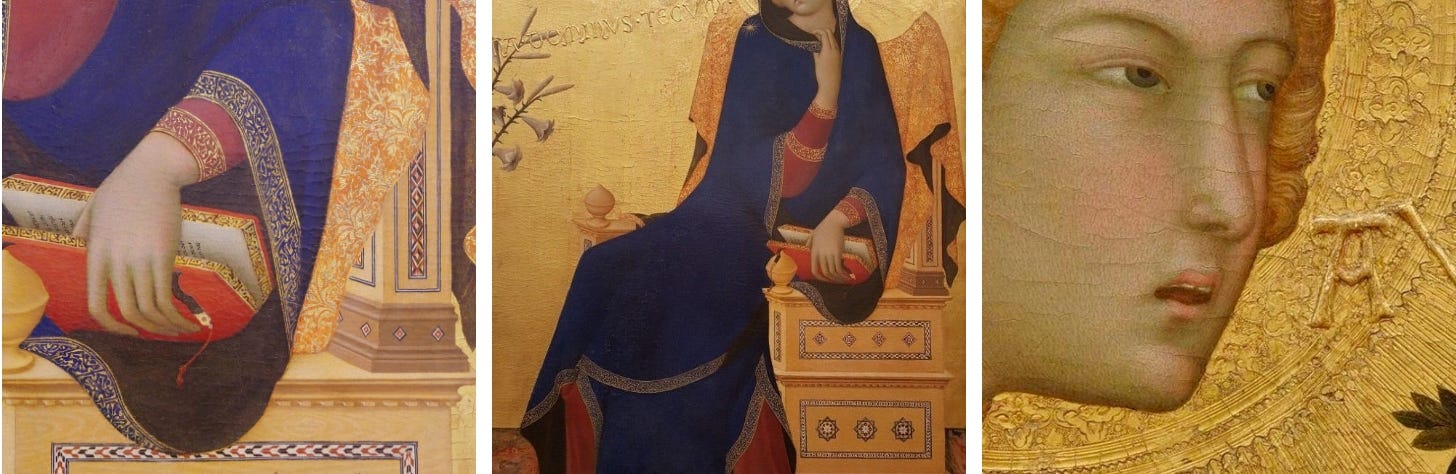

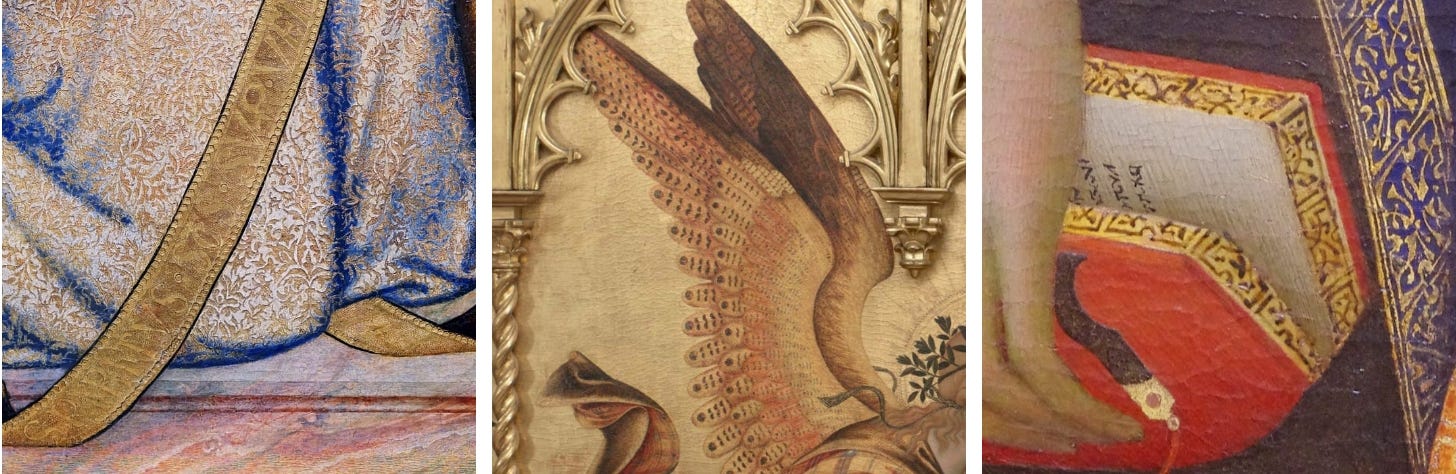

Back to SienaHave you ever seen a painting so graceful it practically sings? That's the magic of Simone Martini, an absolute rockstar of the Italian art scene in the 1300s. We might have an idea about Gothic art that is all flowing robes, pointy arches and stained glass windows. But Simone’s work set the standard for central Italian Gothic painting as a unique form, and brought it to the rest of Europe during his stay in Avignon as painter to the popes. We have already covered the Italian Trecento period a little. We’ve got a post from a couple of years ago that introduces it generally, and we’ve covered the great master Duccio di Buoninsegna in last week’s “Artist Focus” free post. So today we’re going to take a look at the “other” greatest master of the Sienese Trecento, and the Italian branch of the International Gothic, Simone Martini. Annunciation photo featureIf you know his work at all, it’s probably for this Annunciation, currently held by the Uffizi. It’s an extremely difficult painting to photograph because the background is all gold, and it distorts the camera’s efforts to get the colours right and messes with the light balance. The blue of the Virgin’s robe, for instance, is certainly not black or indigo, but the usual brilliant ultramarine. Fortunately, one of the editors of the Smarthistory website, Dr. Steven Zucker, has taken some extremely high quality close-up photos (that the Uffizi should take a hint from) and posted them for public use. They give about the best indication of the colours available online.  I know we've covered this painting many times, but can we really get enough of it?

Extreme closeups of the work gives a distant inkling of the absolute technical mastery.

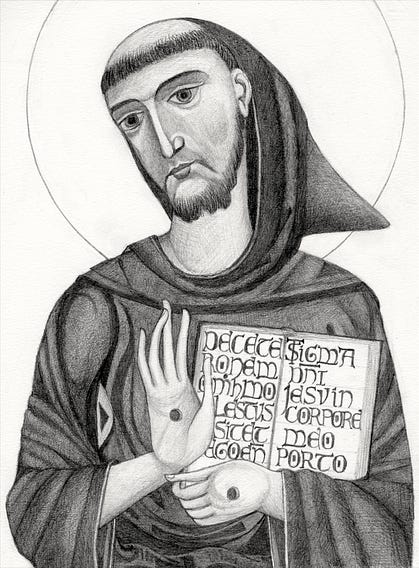

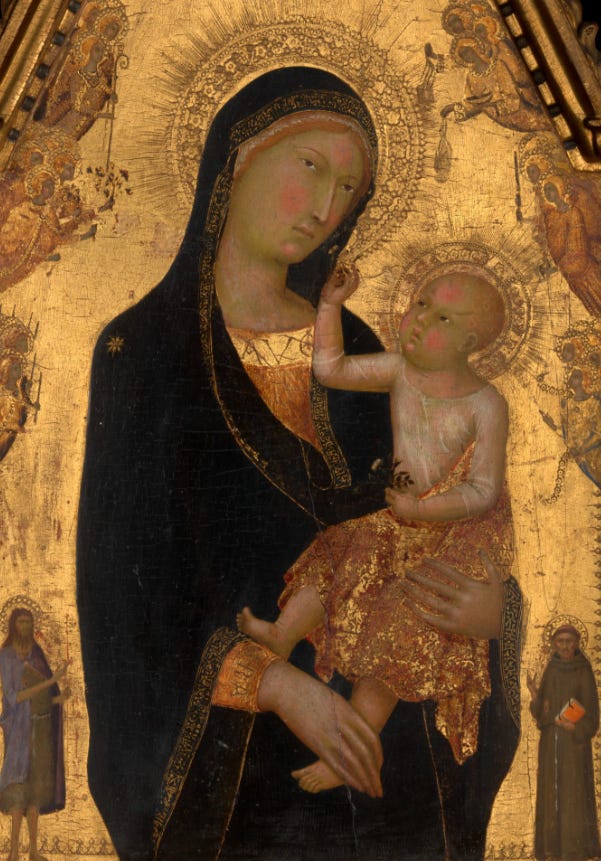

The Sacred Images Project looks at art history and Christian culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art.A big thank you to all who have signed up as free subscribers, and hello to our new paid members. Your contributions not only make it financially possible for me to continue this work, but are a tremendous encouragement to me that other people out there take these subjects as seriously as I do. This is my full time work, and I rely upon subscriptions and patronages from readers like yourself to pay bills and keep body and soul together. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable ebooks, high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.I hope you will consider taking out a paid subscription to help me continue and develop this work.(For those in straightened financial situations, fixed incomes and vowed religious etc., I’m happy to help. Drop me an email explaining and I can add you to the complimentary subscribers’ list.)The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio site, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.Like, my drawing in the Duecento (13th century) style St. Francis of Asissi…Simone Martini leads the Italian GothicWhile Gothic art dominated Europe, Italy had its own distinctive artistic language, that art historians refer to as the Trecento.¹ It shared some Gothic themes, but Simone and his peers brought to the Gothic a more delicate touch, and a more direct connection with the Byzantine forms, including a great deal of gold. Born in Siena around 1284, Simone Martini's exact origins remain somewhat obscure. He likely apprenticed under a master painter, possibly the renowned Sienese artist Duccio di Buoninsegna and is thought to have been influenced by the Florentine, “Father of the Renaissance,” Giotto di Bondone. By 1315, his career was established enough to have received a commission by the commune of Siena, his early masterpiece, the "Maestà" fresco, still held in Siena's Palazzo Pubblico, the painting that dedicated the city state of Siena to the Virgin. Maestà, Simone Martini 1315 - 1321, the “national portrait” of the Sienese city state

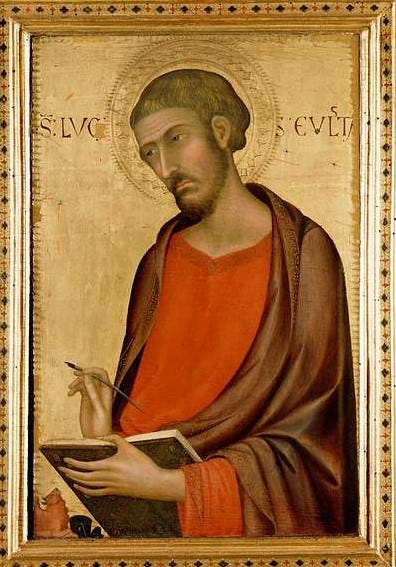

Some very Duccio-esque faces here… Martini's career blossomed throughout Italy. He travelled widely, accepting commissions in Assisi, Naples, and Rome. His work attracted patrons across Europe, including King Robert of Anjou in Naples. He is considered a central figure in the International Gothic style, a movement known for elegance, intricate details, and lavish use of gold leaf. Some of his most celebrated works, like the Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus (the Uffizi Annunciation, above), were created in collaboration with his brother-in-law, Lippo Memmi. Martini brings Trecento elegance to AvignonIn 1339, Martini settled in Avignon, the papal seat at the time. There, he not only found a new artistic haven but also befriended the poet Petrarch. Martini’s stay in Avignon, beginning around 1335, brought the refined aesthetics of the Sienese School to the cosmopolitan court of Pope Benedict XII,² noted as a patron of the arts. In its time as the seat of the papacy, Avignon was a vibrant cultural hub attracting artists and intellectuals from across Europe.  Martini's work there included frescoes for the Papal Palace and altarpieces, which demonstrated his characteristic elegance, intricate detail, and innovative use of colour. His presence in Avignon helped disseminate the International Gothic style, blending Gothic elegance with local influences, and solidifying his reputation as a master painter. This period also facilitated a broader exchange of artistic ideas and styles, influencing the trajectory of European art in the 14th century. Martini’s Avignonese followersSimone died in Avignon in 1344 but left behind a following of painters who learned his lesson to varying degrees. Among these the most notable was Matteo Giovannetti, originally from Viterbo. Giovanetti’s frescos decorating the papal apartments are still preserved. These fundamental examples of non-religious, decorative painting, among the first in Europe, show a depiction of nature that is both idealised and natural, in keeping with the Trecento Gothic principles. Some Simone Martini eye candyIn these panels, the influence of the earlier Byzantine style is easily discernible. Simone Martini's use of Byzantine elements is a hallmark of his style, blending the ornate and the abstract, symbolic spiritual to create a sense of divine presence. Influenced by the rich Byzantine tradition prevalent in Siena, Martini incorporated elements such as gold backgrounds, which symbolized the heavenly realm and added a luminous, ethereal quality to his paintings.  Intricate patterns and detailed ornamentation in garments and halos are Byzantine elements brought to a Gothic peak. His figures have a serene and graceful linearity and symbolic stylisation, but start from the canonical representations of Byzantine iconography, emphasising mystic spirituality over naturalistic representation.  The Gothic elegance of the Sienese School blended with the ancient canons of Christian sacred art created a unique visual language that brought forward the spiritual and aesthetic sensibilities, bridging Eastern and Western artistic traditions.

1

Meaning "300," an abbreviation of “milletrecento” or 1300s.

2

The third Avignon pope. He reformed monastic orders and opposed nepotism. Finding himself unable to his capital back to Rome, Benedict started the building of the great papal palace at Avignon. You’re currently a free subscriber to The Sacred Images Project: Early Christian Art and Culture. To see all the posts, deep dives, videos, chats and receive access to special downloads, upgrade your subscription. It’s just $9/month. |